Mozambique History

The Bantu People

The Bantu People & Mozambique

The Bantu, a vast linguistic and cultural group comprising over 500 ethnic subgroups, represent one of the most transformative forces in African history. Originating from West-Central Africa, their migrations reshaped the continent's demographic, linguistic, and societal landscape over millennia. In Mozambique, where the majority of the population—estimated at over 35 million in 2025—traces descent from Bantu ancestors, their legacy is profound. This article explores the Bantu's origins, migrations, and enduring impact on Mozambique, from pre-colonial kingdoms to modern ethnic identities, drawing on archaeological evidence and historical scholarship to highlight their role in forging a resilient nation.

Origins and Timeline of the Bantu Migrations

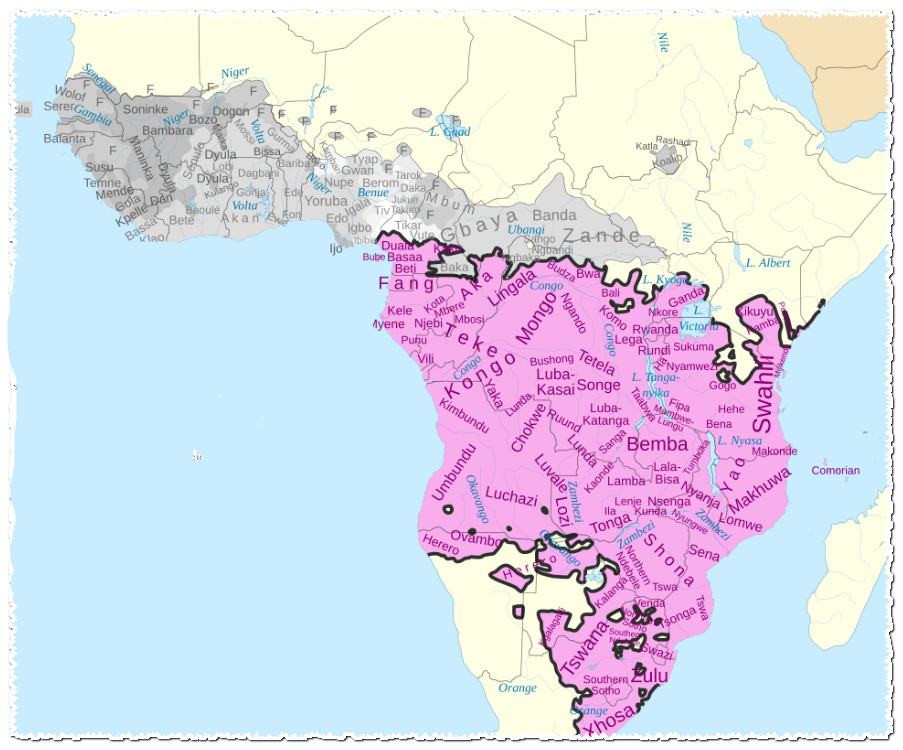

The Bantu trace their roots to Proto-Bantu-speaking communities in the border region between southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon, diverging from the broader Niger-Congo language family around 5,000–4,000 years before present (BP), or approximately 3000–2000 BCE. Initially hunter-gatherers, these groups gradually adopted agriculture and ironworking, though early expansions were not driven by a "military-industrial package" as once thought—ironworking played a minor role initially, with farming evidence emerging later.

The migrations unfolded in waves: the first from West Africa into Central Africa and the Great Lakes region during the 2nd millennium BCE; a second into East Africa in the 1st millennium BCE; and a third southward into Southern Africa, including Mozambique, in the first half of the 1st millennium CE (around 1–500 CE). By 300 CE, pioneering Bantu groups had reached areas like KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, with Limpopo Province settled by 500 CE, indicating a parallel advance into Mozambique's coastal and inland regions. The process largely concluded before 1500 CE, spanning over 3,500 years and altering Africa's makeup forever.

Causes and Routes of Expansion

Several factors propelled the Bantu migrations: resource exhaustion (e.g., depleted agricultural land and grazing areas), overpopulation, famine, epidemics, competition for resources, intertribal warfare, climate change impacting crops, and a exploratory spirit. Climate events, such as the rainforest's destruction around 2,500 BP, created savannah corridors that facilitated southward movement.

Routes began in the Niger River savannah and rainforests of southern West Africa (modern Nigeria, Cameroon, Gabon), branching into West Bantu (southern West Africa) and East Bantu (Great Rift Valley) paths. For Mozambique, the eastern route via the Great Lakes and coastal plains was key, with migrants crossing the Rovuma River in the north and advancing southward to the Maputo region by the 3rd–4th centuries CE. This gradual expansion involved small-scale farming communities, debunking myths of rapid, militarized conquests.

Arrival in Mozambique and Interactions with Indigenous Peoples

Bantu groups arrived in Mozambique during the third wave, settling along the coast before moving inland, as part of the broader push into Southern Africa. Archaeological evidence, such as Kwale wares (pottery) dated 200–300 CE in nearby KwaZulu-Natal, suggests early presence in southeastern Mozambique, with sites like the Rufiji Delta (100 BCE–300 CE) indicating coastal influences.

Upon arrival, Bantu migrants encountered indigenous Khoisan (San hunter-gatherers and Khoikhoi pastoralists) and other groups, leading to complex interactions. Relations involved intermarriage, cultural exchange, and sometimes displacement through conflict, with Bantu iron tools and farming techniques providing advantages. Genetic studies show significant gene flow, including adoption of click sounds in southern Bantu languages from Khoisan influence. Contrary to older views of fragmentation, Khoisan groups were already geographically distinct, and Bantu absorption often enriched both cultures.

The Bantu introduced iron-smelting, pottery, and crops like bananas and yams, transforming subsistence practices and enabling population growth. This fostered village-based societies, setting the stage for economic surpluses and social hierarchies.

Formation of Pre-Colonial Kingdoms and States

The Bantu's technological edge and agricultural innovations spurred the rise of complex societies in Mozambique. By the late 1st millennium CE, states emerged along river valleys and trade routes, linked to Indian Ocean commerce.

Key kingdoms include:

- Great Zimbabwe (11th–15th centuries CE): Centered in the Zimbabwe plateau but influencing northern Mozambique, this state featured massive stone enclosures (e.g., Great Zimbabwe ruins) and thrived on gold, ivory, and metal trade with Swahili Arabs via coastal ports like Sofala. Its decline around 1450 CE due to overpopulation and resource depletion led to successor polities.

- Mutapa (Mwene Mutapa) Empire (15th–17th centuries CE): Emerging as a northern offshoot in the Zambezi Valley, Mutapa expanded under rulers like Mutota and Matope, forming a federation with tributaries such as Barue and Manica. It controlled gold trade routes, blending Bantu governance with spiritual authority, and interacted with Portuguese explorers from 1505 onward.

These states demonstrated Bantu ingenuity in political organization, with oral traditions and Portuguese accounts (e.g., 1552 shipwrecks) describing agro-pastoralist communities ruled by kings ("Inhaca") and chiefs ("Inkosis").

Cultural and Linguistic Legacy

The Bantu migrations homogenized Southern Africa's cultural fabric, spreading over 500 related languages spoken by 240 million people today, including Mozambique's dominant tongues like Makhuwa, Sena, and Tsonga—all Bantu derivatives. Linguistic similarities, such as shared vocabulary and grammar, reflect a common origin, while admixtures (e.g., Khoisan clicks) highlight hybridity.

Culturally, Bantu influences persist in Mozambique's art (rock paintings blended with indigenous styles), music (timbila xylophones), and social structures (clan-based systems). Rituals for ancestors and environmental harmony, introduced by Bantu, underpin modern traditions, while farming techniques sustain rural economies.

Modern Relevance in Mozambique

Today, Bantu descendants form the ethnic backbone of Mozambique, with groups like the Makua (largest), Tsonga, and Shona embodying this heritage. Their migrations laid foundations for national identity, influencing everything from language policy (Portuguese official, but Bantu languages recognized) to cultural revival post-civil war. Sites like Manyikeni and the legacy of Mutapa inform tourism and education, fostering pride amid challenges like climate change—echoing ancient adaptations.

In essence, the Bantu's journey into Mozambique was not just migration but a catalyst for innovation, state-building, and cultural fusion, shaping a nation resilient through centuries of change. As Mozambique navigates its future, this legacy remains a vital thread in its historical narrative.